The Power of Powers of Ten

How the Eames’ experimental film changed the way we look at Chicago—and the universe.

Perhaps no American city appreciates being at the center of the universe more than Chicago. Workmanlike and down-to-earth the majority of their days, Chicagoans savor those moments when all roads lead to the prairieland. Even as we grapple with an international reputation for our inexcusable crime rate, we all breathed a sigh of relief when this summer’s NATO summit, the first on U.S. soil outside the Beltway, showcased the city’s international reach without ravaging the Loop. During this year’s election night celebrations inside McCormick Place, the country’s largest convention center, we were afforded another opportunity on the world stage.

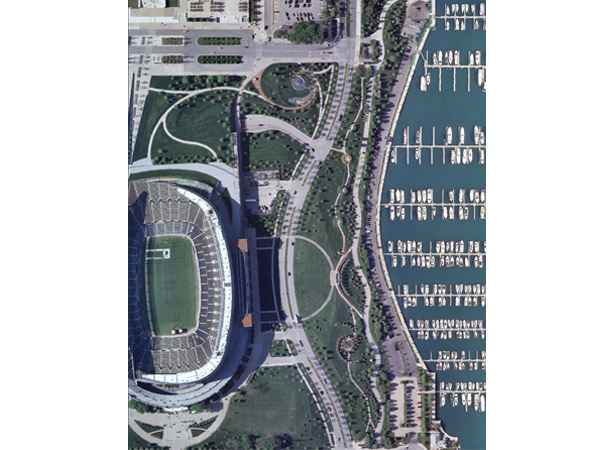

On election night, hoping I might encounter some of the same crowd spillover that defined the camaraderie and openness of Obama’s victory rally in Grant Park in 2008, I was confronted instead with the usual convention-center congestion: street closings, revolving doors spitting out those without tickets, road flares glowing in the crosswalks. Shut off from the monolithic superstructure housing all the fun, I wanted to rip the roof from its foundation and peer down at the spectacle within. While McCormick Place trended on Twitter worldwide, I imagined distant onlookers pinpointing the exact spot where I was standing on Google Earth, trying to get their bearings. And I was reminded of the power of Powers of Ten, the 1977 experimental film that surveyed these grounds from above as never before.

Has Chicago, or any city, been captured as beautifully and precisely on film? Has a sequence spurred more awareness of the vastness of space than the now-classicPowers of Ten zoom? And would there even be a Google Earth to tinker with had this masterwork not poured from the minds of Charles and Ray Eames?

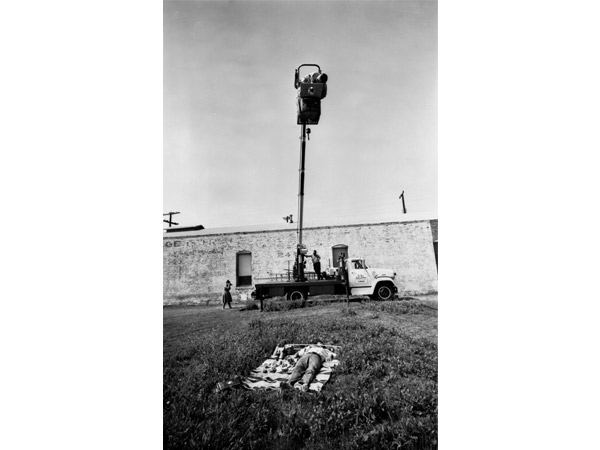

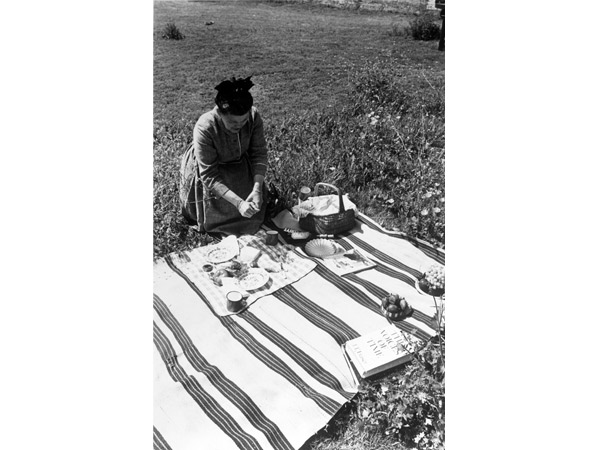

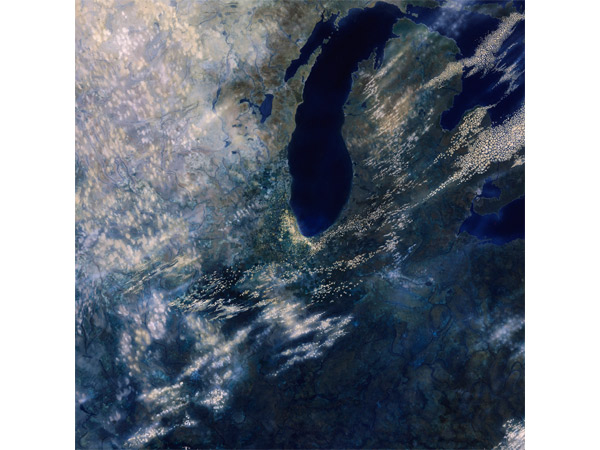

The film’s premise is deceptively simple. For nine minutes, the narrator, physicistPhilip Morrison, guides the viewer on a fantastic voyage that begins with an overhead shot of a couple lounging by the lake in a Chicago park, a spot close to Soldier Field, home of the Chicago Bears, and equidistant to McCormick Place and Grant Park. The camera then tracks back above the cityscape and up through the stratosphere, reaching back to the edge of the known universe. We then drop back down to Earth, Felix Baumgartner-like, and reunite with the parkgoers. The persistent camera continues its descent, now plunging past dead skin cells in one of the picnicker’s hands before isolating a single proton in the nucleus of a carbon atom, plugging away in a tiny blood vessel.

Endlessly imitated in commercials and Hollywood films (Men in Black and Contactamong them) and predating Google Earth (and Google Mars) by decades, the zoom continues to captivate viewers, leaving them either awed or overwhelmed by journey’s end. Paul Schrader, a devout admirer of the original “rough sketch” Powers of Ten film that predated the final Chicago-based version by a decade, wrote that the interstellar roller-coaster ride allowed the viewer to “think of himself a citizen of the universe.” Charles Eames wanted the film to appeal to a 10-year-old as well as a physicist and claimed the goal was for viewers to experience a “gut feeling” about dimensions in time and space. The message was received. In 1998, Powers of Tenearned a spot in the National Film Registry of the Library of Congress, the same institution that claims over 1 million archival items gathered from the Eames Office after their doors closed in 1989. That same office space in Venice, Calif., was lateroccupied by Facebook. When the Eameses established a temporary office in the Merchandise Mart in Chicago, circa 1950, in a previously unused, Charlie Kaufman-esque top-floor space, even the owner of the building, Sargent Shriver, wasn’t quite sure what they were up to. But the Eameses were once again ahead of the curve. Sixty years later, their makeshift office will soon be home to the Chicago offices for Google.

This year marks the 35th anniversary of Powers of Ten, and Dec. 15 is the centennial of Ray Eames’ birth. (Ray completed her own remarkable powers of 10 journey in 1988, passing away 10 years to the day after Charles, her husband of 37 years.) The magic of their mind meld has been preserved in Beautiful Details, a spectacular new book exploring the Eames legacy that will enliven, or perhaps leave you questioning, your coffee table and the furniture that surrounds it. Perhaps even the cosmos.

The book, the first authorized work of its scale, was spearheaded by Eames Demetrios, grandson of Charles and Ray and principal of the Eames Office, a gallery and educational space now located in Santa Monica, Calif. In Beautiful Details, Demetrios notes that Eames films were never outsourced. “[Charles and Ray] never hired a film production company to make the films for them—even a technical tour de force like Powers of Ten.” Having harnessed the collective brainpower of the Eames Office, the film was completed with the financial support of IBM, which shared Charles and Ray’s concern that American students were falling behind in math and science and needed to be stimulated.

Subtitled “A Film Dealing With the Relative Size of Things in the Universe and the Effect of Adding a Zero” and based on the 1957 book Cosmic View by Kees Boeke, the guiding principle of Powers of Ten is that every 10 seconds our distance from the initial scene—the couple in Chicago, captured in an aerial shot 10 meters wide—becomes 10 times greater before reversing course to explore the galaxies within the human body.

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario